Shelly Bond is a comics superhero

OK, she may not wear a cape, but in the ways that matter, Shelly Bond has been a force for good in the world of comics and graphic novels. When it comes to making great comic books and graphic novels, there are few people who have accomplished more—or know the industry better—than her. Bond has spent nearly 35 years working in comics publishing, lending her expertise to cult favorites, pop-culture phenoms, and critically acclaimed works.

Her resume features big names like DC Comics/Vertigo, Hugo and Eisner awards, and a longtime partnership with Neil Gaiman.

Or as the website for Off Register, the imprint Bond co-founded with her husband, Philip Bond, describes her professional history: “Editor/Idea Generator, Mad Scientist, and Master Control at DC Comics/Vertigo for over 20 years. Editor of Hugo and Eisner Award-winners The Sandman: Overture by Neil Gaiman & JH Williams III and Fables by Bill Willingham, recipient of 14 Eisner Awards and 150 consecutive issues. Editor of Bitter Root, winner of the 2020 Eisner Award for best continuing series.” That’s not all: before they hit small screens as TV series iZombie (Chris Robertson and Michael Allred) and Lucifer (Mike Carey and Peter Gross) were comics created under Bond’s guidance.

But what does a comics editor do? And how does their work benefit artists, writers, and readers?

“Comics editors are a special breed of human. They’re able to coax mad genius writers into turning a script in on time, and direct talented artists towards the best way to showcase their skills, while simultaneously conducting the complex orchestra of colorists, letterers, and designers who are vital to putting out a successful comic,” says CCAD Comics & Narrative Practice Chair Laurenn McCubbin.

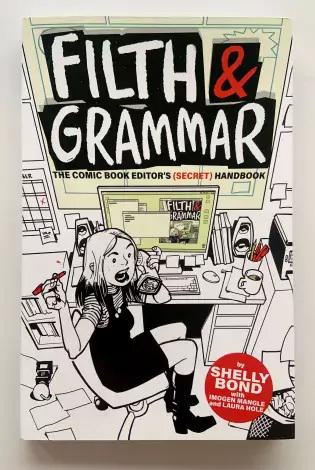

And Bond literally wrote the book on comics editing. No, really—in 2022, she published Filth & Grammar: The Comic Book Editor’s (Secret) Handbook, described as “160 pages chock-full of pro tips, pet peeves, dos and don'ts" shared via comics and prose.

So when Bond talks, you’re wise to listen.

And when Shelly Bond visited Columbus College of Art & Design to talk comics, we took notes.

Bond’s stop to talk with a group of Comics & Narrative Practice students came in conjunction with Cartoon Crossroads Columbus, an annual citywide showcase of the best of cartoon art in all forms. Bond discussed her career in comics and reviewed some of the students’ works-in-progress.

“Being able to work with an editor as talented and well-regarded as Shelly Bond was a special experience for our students,” says McCubbin.

But even if you weren’t among those who were able to experience Bond’s editing chops firsthand, we’ve got you covered. Whether you’re a beginner just starting to explore making a comic book or graphic novel or someone looking to refine their creative works, we’re sharing some key takeaways from her presentation.

Expert tips from Shelly Bond on making a comic book

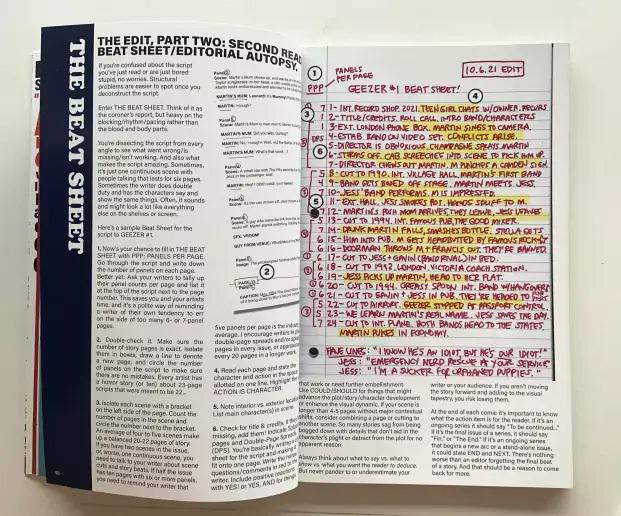

1. Beat sheets are crucial in creating a compelling story.

As part of her visit to CCAD, Bond provided a small group of CCAD Comics seniors with personal, detailed edits on their beat sheets. (Beat sheets, if you are unfamiliar, are brief outlines that tell a comic’s story, from the beginning to the end, with callouts for pivotal points in the plot.) The students then used the beat sheets to work on the scripts for their senior capstone comics, the culmination of all that they’ve learned in the Comics major.

As an editor at Vertigo Comics, Bond encountered writers who didn’t want to create or share beat sheets. “For some reason, there are writers who are just like, ‘I’ll just make it up as I go,’” she says. But, says Bond, editors who know their stuff will push back.

A good editor will tell a writer that they need to know the story direction from the start, Bond says. “A great editor will let you change an ending. … But you need to come to the table knowing what you’re doing,” she continues.

2. Beware of “midpoint sag.”

As you’re developing your story, consider ways to keep the reader engaged. You want to start off strong—and, of course, have an exciting ending, but the middle matters, too. Midpoint sag, aka a slowing in your storytelling, is a concern. To combat that sag, “I always tell people to do something unexpected in the midpoint of their book,” Bond says.

3. Cut away from your protagonist.

You want to create characters that your readers are invested in. But Bond says she’s also a fan of scene cuts and leaving the protagonist for a bit. “When you cut away from them, you allow the reader to miss the main character,” she says.

4. Your story can have multiple characters—but exercise some restraint in their numbers.

“Having a lead character and three to four characters is fine,” says Bond. “Any more than that, and you should consider combining some of them.”

5. Change the scenery.

In the same way that a comics creator should consider switching things up around their main character, so should they include a mix of scenes within a story. “For me, on a 22-page story, I need at least 2–5 scene changes, or I’m bored,” says Bond.

6. Make your work visually interesting—in a way that makes sense.

Layout and imagery matter. They help guide your reader through a story, provide unexpected moments, and impact the pacing of different moments. And they also impact how clear—or unclear—story elements are for readers. “Think about the visual dynamic, how we move the eye from left to right, top to bottom,” Bond says.

(Relatedly: Bond’s booklet Remake/Remodel instructs creators to be mindful of characters’ placement on the page and how it relates to dialogue. “The first person who speaks should always sit on the left side of the panel. Reading order is left to right, top to bottom,” the book—which also advises against crossed tails on word balloons—instructs.)

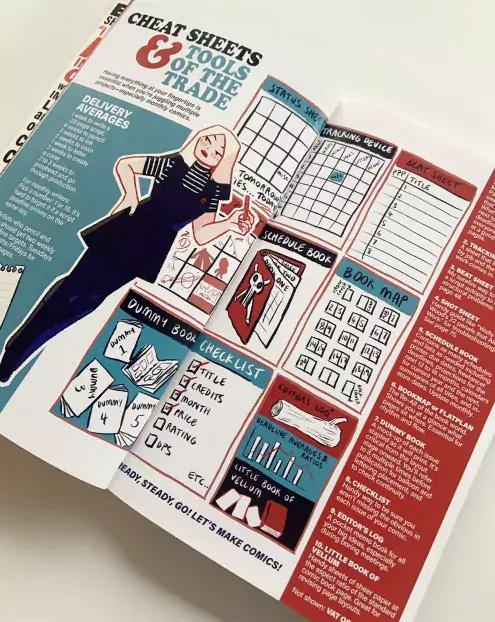

7. A book map provides perspective on how each element supports the overall piece.

A book map visually depicts your 22-page script (plus front and back cover), showing where the pages sit in relation to each other. A book map helps with your story’s rhythm and flow—and supports its telling even before page 1.

For instance, Bond says, when she was creating her newest work, Fast Times in Comic Book Editing, the book map helped guide her into starting a story sequence on the end pages—“so the action starts at the moment you open the book,” she says. Often, when you’re going through the process of creating and then editing a work, some material ends up hitting the cutting room floor. But, says Bond, you can sometimes find ways to use some of that “extra” material in unexpected ways that support your storytelling.

“When you are making a book, everything matters,” says Bond. “Nothing is arbitrary. You are in charge.”

A good comics editor like Shelly Bond will make your work better.

They’re your first reader, and they’re there to help you develop your story and the story arc, fine-tune pacing, assist with dialog, ensure there is continuity of a story and its characters within and across issues, provide feedback about layout and art—and, oh yeah, rid your work of typos, misspellings, grammatical errors, and more.

An editor also works as a project manager of sorts, keeping the work moving along from the initial concept to the final product and ensuring that the art and the language complement each other, which makes writers, artists, colorists, letterers—and, most of all, readers—happy.

Even if you missed Shelly Bond in person, you can still catch recordings of her at CXC.

While the workshop held at CCAD was held for students to hear directly from Bond as part of their classroom experience, here’s some good news: You can hear more from the editor herself in this recording from her CXC talk, CCAD Spotlight on Shelly Bond, where she joined McCubbin in a career-spanning interview. (In addition to being a featured speaker at CXC, Bond has a longtime connection to McCubbin, who, in the early 2000s, McCubbin drew an issue of Madame Xanadu written by Matt Wagner and edited by Bond.)

Bond made McCubbin redraw one Madame Xanadu panel “four or five times,” Bond recalls in the video. “... And then she thanked me later when she saw her work in print and it looked magnificent. Editors are bossy and we seem mean, but you’ll thank us later.”

If you want to be a comics illustrator, writer, letterer, colorist, publisher, or storyboard artist, there’s no better place to be than CCAD, where you can earn a bachelor’s degree in Comics & Narrative Practice.

While CXC is a once-a-year event in Columbus, CCAD’s Comics & Narrative Practice program hosts workshops every week featuring a range of industry leaders, from the major publishers to indie imprints and even manga-ka from Japan.

And that’s not all. CCAD’s Comics faculty are active in the industry, with connections to heavy hitters like Marvel and DC, creator-owned stalwarts Image Comics, indie comics standout Fantagraphics, and children’s book publishers such as Random House.

Taken together, students’ close work with faculty; workshops with some of comics’ greatest creative minds; and experiential learning through students’ active participation in comics making, marketing, and selling, prepare CCAD students for industry success—and creative fulfillment.

Image credits: Images two, three, four, seven, and eight courtesy of Ray La Voie for Cartoon Crossroads Columbus.